Draft and The Dons

After finishing at Michigan after the 1947 season Ford was not drafted by the NFL. While the NFL was technically re-integrated in 1946 when Kenny Washington was signed to the Rams, this was forced by a policy that required that Los Angeles teams be integrated to use city facilities. The Rams, relocating from Cleveland, therefore had to sign Kenny (and later Woody Strode) to make use of the Los Angeles Coliseum; but they, and other league teams, didn’t need to draft or add to their black players.

Ford was selected, however, in the third round of the 1948 AAFC Draft by the Los Angeles Dons who, ironically, had ended up in a dispute over their use of the same Los Angeles Coliseum in their inaugural 1946 season when they employed no black players. In 1947 Ezzrett “Sugarfoot” Anderson – an African-American veteran from the Hollywood Bears (the same Minor League team for whom Washington and Strode previously played) – integrated the Dons. Ironically, the Dons had lobbied hard in February of 1948 to bring in Ford’s former Michigan head coach Fritz Crisler as their head coach. GM Harry Thayer asserted, “Crisler can write his own ticket”. Crisler declined the Dons’ offer and just a month later, in March, stepped down as Michigan Head Coach. This ended Crisler’s coaching career, but he stayed with the school as Athletic Director, a position he would hold for another two decades, becoming a beloved Wolverine whose basketball arena was later named after him.

In 1948 with the Los Angeles Dons Ford was an immediate, if inconsistent, contributor. Dons’ new coach Jim Phelan – a successful college coach who would ignominiously go on to one of the worst winning percentages in league history, including consecutive one-win seasons with the Yanks in ’51 and Texans in ‘52 – implemented a unique offense for the 1948 season. Dubbed the “Phelan Spread,” it was designed to highlight the skills of passer Glenn Dobbs and pass catchers Burr Baldwin and rookie Len Ford. As a receiver, Ford was third on the team in receptions but second in both receiving yards and receiving TDs, the latter two being good for eighth and fourth in the AAFC overall. There were some early season issues with Ford's hands and “second rate pass catching, or non-catching, by Len Ford . . .” but as the overall numbers reflect this was not enough to keep him off the field as an offensive weapon. Going back to his Michigan days Ford liked to go for one-handed catches. That sometimes allowed him to stretch out for the spectacular catch but could backfire with drops. He had a long reception of 53-yards against San Francisco and another 50-yarder later in the year while averaging just under 20 yards-per-catch, impressive for a man his size. These numbers and the descriptions speak to the amazing size-speed combo Ford was, he could go for 53-yards or, in an October bout with the Buffalo Bills, “take the ball from Bill fullback Schuette on the 5 and drag the latter across the goal.”

Primary sources are scant for the Dons of this era, but evidence suggests that Ford was a defensive impact-maker as a rookie as well. While Ford didn’t start in their opening game shutout of the Chicago Rockets, he clearly made an impact. On the steamy August day in Soldier Field, former Notre Dame QB Angelo Bertelli could do nothing as, according to Dick Hyland of the Los Angeles Times, “Dale Gentry, Bob Nowaskey, Burr Baldwin and Len Ford contributed greatly to this defensive work by rushing Bertelli until he was dizzy.” the following week Don Coach Jim Phelan saw enough of Ford that he was placed into the starting lineup for their tilt with the Browns. Wally Willis was quoted in the Oakland Tribune saying, “They put on a display a trio of defensive men who take a back seat to no one. By name they are Len Ford, a giant end who played with Michigan last year . . . Wally Heap . . . and Bob Nelson.” Red Dawson, Buffalo Bills head coach went so far as to say Ford was, “the best he’s ever seen. Exceptionally fast.” By November of his rookie year the Dons’ brass believed Ford, “belongs on the Conference first-team selection. Unlike other star ends who have always made the club by catching passes, Ford plays both offense and defense and is particularly great at both.”

At season’s end Lenny was named Second-team All-AAFC defensive end, behind established Yankee right end Jack Russell. It’s noteworthy, however, that the team was selected by coaches Carl Voyles of the Brooklyn Dodgers and Red Strader, the coach of Jack Russell’s own Yankees. The AP Team selected from combined AAFC and NFL representatives awarded Ford honorable mention as a rookie.

Off the field, Ford was the talk of the town in Los Angeles, enjoying access to all that Hollywood had to offer. Described as the “Big Brown frame . . . the whispers of many a girl.” Or the man who was, “breaking more hearts than unrequited love.” This early off-the-field activity may have distracted from his on-field exploits, but later in his career they would take a greater toll as Lenny aged.

More first-hand evidence can be seen of Ford’s performance in 1949 as a Don. Again, Ford was a reliable pass catcher, though his numbers largely matched his rookie figures in an era where pass-catching numbers were increasing dramatically. The Dons’ passing overall was down in 1949, and Len’s flat figures now lead the team. His 36 receptions, including a team record eight in a late-October match against the Chicago Hornets, were aided by numerous targets from rookie quarterback George Taliaferro whose shoulder Ford had separated in that 1947 Big-Ten matchup. On the defensive side of the ball, he was effective again, even seeing some snaps at linebacker in replacement of injured starter Dan Dworsky mid-season. Inconsistency was still an issue in his sophomore campaign as a pro, Los Angeles Times Dick Hyland referring to him as an “in-and-outer . . . looking like a world beater on one play and flattened out on the next by someone his 235 pounds of spring-steel strength should handle with ease.” Later, in praise of left end Burr Baldwin Hyland would say that Baldwin, “makes that big Len Ford look like a No. 1 kind sissy.”

In an October 23 tilt against the Bills, he stuffed a Bill for a 7-yard loss attempting to get around his left end. In the penultimate game of the season, playing near his Morgan State stomping grounds in Baltimore, Ford was the undisputed star of the game and would have been defensive Player of the Week honors had it existed at the time. In the second half, Ford sacked Colt quarterbacks three times and intercepted a fourth-quarter Y.A. Tittle pass, which he returned 45-yards down the sideline. This directly ended two of three late Colt advances and helped maintain the Dons’ margin in an eventual 21-10 road victory.

The 1949 UPI All-Star team again placed Ford in the position of honorable mention, with a clear bias for offensive ends. First-teamers Mac Speedie and Alyn Beals were first-first-second and third-third-first in receptions, yards, and TDs. The Second-team was made up of Alton Baldwin and Dante Lavelli who were second-second-second and tenth-tenth-second, respectively, in the same categories. Ford’s one TD reception likely relegated him to honorable mention along with Jack Russell, who had beaten him out in 1948, but who was also similarly defensive-minded.

To the Browns, 1950 and the Injury

The AAFC regular season wrapped up in late November and shortly after the early-December playoffs the league was defunct, with the 49ers, Browns, and Colts heading off to a newly merged NFL. Respecting that standard football contracts of the day had teams retain rights till June first, Bert Bell organized an AAFC disbursement Draft to distribute players from teams that didn’t survive into the new league, for June second of 1950. This draft was held at the Bellevue – Stratford Hotel on the corner of Broad and Walnut Street in Philadelphia, the same site as the 1950 collegiate draft, just blocks from Bell’s League Headquarters, and a short train ride from Bell’s suburban Philly home.

Going into the draft, Ford was rumored to be highly desired by then Cardinal coach, VP and GM Curley Lambeau, new Ram head coach Joe Stydahar and new Packer front man Gene Ronzani. Paul Brown recounted later that Lenny was rumored to have an “attitude problem,” which may have impacted his draft status, but Brown believed it was nothing more than his hatred of being on a losing team. Ford’s Dons’ teammate, the Hollywood-born Cal grad tackle Bob Reinhard had signaled his intent to stay on the West Coast, regardless of who picked him. In a work of draft-day wheeling-and-dealing, Lambeau passed on Lenny to select Reinhard, then trading the star back to the West Coast Rams in exchange for three players Jerry Cowhig, Tom Keane, and Bob Shaw.

But after an excellent AAFC career which saw him named First-team All-AAFC in both 1948 and 1949, Reinhard would start just seven games for the Rams in 1950 before his football career was over, due to chronic back problems. Of Cowhig, Keane, and Shaw, only Keane would come to any acclaim, posting a couple impressive years as a DB picking off 10 passes in 1952 and then making All-Pro with 11 interceptions for the Colts in 1953. Ironically, this success came after being released by the Cardinals in September 1950 prior to the start of the season. He then caught on and played two years for the Rams before seeing success with the 1952 Texans and 1953 Colts. Ford’s second-round selection by the Browns was viewed with some surprise by the local papers, but none of the earlier picks would compare to what was to come from Ford. Only Lou Creekmur, of those picked prior to Ford, would make the Hall of Fame. Ford’s official signing with the Browns was announced by the team on June 28.

From his very first practices with the Browns Lenny drew praise, with Coach Brown’s first observation of the 1950 team being that, “Len Ford is a terrific end” and that “he splatters ‘em”. Of the 1949 starting defensive ends, only George Young returned. John Yonakor – a star in the early AAFC for the Browns – had come under criticism and was allowed to leave prior to the season; this left Ford as the presumptive starter, and he took advantage. The Browns typically deployed the 5-man line of George Young, John Kissell, Bill Willis, John Sandusky, and Ford from left to right across the line. Horace Gillom and Bob Oristaglio would see time as backup ends and Derrell Palmer and Chubby Grigg as backup tackles. As would transpire over the following few years, the Brown would tinker with a 4-man line and occasional formations with Willis and Ford aligned side-by-side.

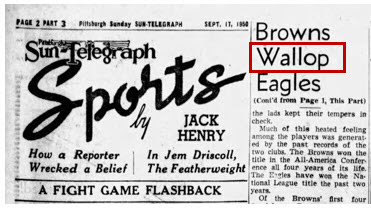

As September rolled around, the Browns prepared for what would be the biggest regular season game in years. The reigning NFL and AAFC Champs were pitted off against each other in Philadelphia, the entire world expecting a decisive Eagle victory. But on Sunday, September 17th the day following the game, the headlines showed the world was wrong.

Crush, Trounce, Rout, Wallop, Drub pick a verb; the Browns immediately staked their claim amongst the best in professional football. So overwhelming was the Browns defense against the Eagles attack that towards the end of the game the Eagles actually ceased using the T-Formation, failing back to their “Z-Wide Formation” a desperation spread formation. The Eagles suffered 18-yards “lost attempted pass,” likely two sacks but possibly one long sack, and the focus of press coverage was on the Browns spectacular offensive play. Ford received some notice for penalties, one a clipping penalty negating a long TD run by halfback Don Phelps, another a roughing the passer penalty for 15 yards. In fact, other than the scoreboard, the most notable disparity in numbers was the Browns 12 Penalties to the Eagles three. One wonders if the NFL refs had their fingers on the scale, albeit to no avail.

The following week the Browns trounced the Baltimore Colts, the weakest of the holdovers from the AAFC to the NFL, Lenny logged his first known sack in the NFL, a 10-yarder on Y.A. Tittle (no play-by-play or full game film of the first game against the Eagles are available to account for the 18 “yards lost attempting to pass.” In week three, the Giants and Browns met in Cleveland in what would be the Browns first loss in the new league. The Giants were a strong squad and – similar to the Browns – had a defense that benefitted greatly from an influx of AAFC talent, obtaining a future Hall of Famer in tackle Arnie Weinmeister and an All-Pro in defensive back Otto Schnellbacher, each from the AAFC’s New York Yankees. The 6-0 shutout at home saw the Browns throw four interceptions without a TD and lose the turnover battle 5-1. The game is best characterized as an offensive misfire rather than a defensive failure. The Browns sacked Conerly four times for 40 yards, and Len came up with his second known sack of the season, a 14-yarder.

In week four at Pittsburgh, the Browns returned to their winning form, however, there was little opportunity for the Browns and Ford to show pass-rushing prowess as the Steelers were still a full-time single-wing team. However, Ford did share a four-yard sack with John Sandusky and Lou Rymkus also took down Joe Geri in a pass attempt for five yards.

Week five would be a defining game of Ford’s career. In week one the Browns dispensed with the 1949 NFL Champs in the Eagles, now they faced the talented but facing 1948 Champs in the Chicago Cardinals. A tough game saw the Cardinals take a 21-10 lead in the early third quarter. This was aided by strict officiating aimed at the Browns, including a dubious Len Ford roughing-the-passer penalty to extend a scoring drive, before the Browns could pull within a TD at 24-17. The Browns came back again and took the lead in the fourth quarter. In the waning minutes of the game, African-American end and punter Horace Gillom was goaded into a scuffle and was ejected from the game. Then, in the final minute of the game, as the Cardinals attempted to come back, Ford made a big play. Lenny logged a 15-yard sack, beating the Cardinals risky blocking scheme which left fullback Pat Harder to handle Ford one-on-one as a pass-rusher, after executing a play-action fake.

|

| Ford lined up wide, offensive tackle aligned to DRT and Pat Harder directly behind QB Jim Hardy, Bill Willis on the Nose in his familiar frog-stance |

|

| Ford gets a free release while Hardy and Harder execute play-action |

|

| Reverse angle: Harder attempts to block onrushing Ford, Willis has beaten him man creating pressure up the middle |

|

| Hardy bails out of Willis pressure, but Ford – unable to be stopped by Harder after building up a head of steam – is there to take Hardy down |

|

| A long 15-yard sack for Ford |

On the ensuing and penultimate play of the game, another passing situation, Harder got his revenge. Again, Ford was allowed a free release from his right end position, but there are three backs in the backfield with Harder still aligned behind center. The scheme no longer required Harder to carry out a play-action, but the 5’11” 200-pound fullback is still one-on-one against the 6’4” 245-pound Ford. As he approached Ford, Harder lead with his right elbow to Ford’s left jaw, and Lenny went down as if he were shot. Lenny stayed down, clearly hurt as a penalty flag flew in. After a short stoppage, he was helped off, having completed his last snap of the regular season. To add insult to injury – literally in this case – the flag was thrown against Lenny, and Ford, not Harder, was ejected, the head linesman, Bill Ohrenberger, informed Coach Brown that Ford had been holding. Coach Brown immediately protested, even prior to viewing game-film, “Ford?” yelled back Brown, “Why, he’s the fellow down on the ground, hurt.”

|

| Ford aligned wide at right end, another free release |

|

| Harder with no play-action responsibilities slides to Ford’s side |

|

| Harder’s right-elbow to Ford’s left-jaw |

|

| Ford immediately goes to the ground |

| A penalty flag flies in just as Jim Martin arrives sacking Hardy for an 8-yard loss and a forced fumble |

|

| Ford is helped off the field |

In the aftermath of the game, NFL Commissioner Bert Bell fined Ford $50 for the incident, based on hearsay, prior to seeing the film. However, Paul Brown protested as Ford was undergoing surgery for the injuries suffered just as he was informed of the fine. Bell, upon understanding that Ford was under the knife after the incident, rescinded the fine. The media also began noting the outsized penalties called against the Browns with headlines like, “Browns in Ideal Position to Protest Officiating in the NFL.” To this point in the season, the Browns had been docked for 463 yards in penalties to their opponents' 263. This rate had the Browns producing 92.6 penalty yards per game, a pace that still today would hold the NFL record over the 2013 Seahawks who averaged 88.4 penalty yards per game. Over the remaining seven games the Browns would still be highly penalized but at perhaps a more reasonable rate of 72 yards per game.

There were concerns of racial undertones to the gameplay as well with both Gillom and Ford ejected. Paul Brown admitted to being “frightened” by thoughts of a rematch later in the year on Chicago’s majority-black Southside home Comisky Park. Commissioner Bell, upon review of the game film, did not see a need to fine or warn Harder, noting that he had a clean bill previously. The New York Daily News would later refer to this incident generally, including Ford’s ejection, as, “The worst decision in Football this past Autumn.” Coincidentally, Harder was bruised up prior to the Browns-Cardinals rematch and was used sparingly in that game.

The following week, irate Browns owner Mickey McBride demanded that the Cardinals cover the remainder of Ford’s salary and his hospital bills. McBride stated that Ford was, “deliberately slugged . . . there is too much slugging going on . . . Ford hadn’t done a thing out of line.” Cardinals President Ray Benningsen was unconvinced, and Coach Curley Lambeau dug his heels in saying Harder, “just put a good shoulder block on Ford.” Chicago and Ohio columnists came out at odds on the situation, the former noting the rough state of play earlier in the game, the latter focused on the final incident. More concerning for the Browns than the penalty situation, however, were Ford’s injuries. Ford had suffered a broken nose, broken jaw, a broken-cheek bone, a fractured bone in his forehead, two lost teeth, and several chipped and loosened teeth. Ford underwent surgery with Browns physician Dr. Vic Ippolito (a former local Case Western Reserve halfback) observing and plastic surgeon Clifford Kiehn presiding, Ford would have his jaw wired shut following the involved procedure.

|

| Len Ford in Oct 1950, the aftermath of surgery for numerous broken bones |

Following a loss in the next week’s rematch against the Giants, the Browns ripped off a 6-game winning streak to enter a playoff and a successful first season in the National League. When the Browns advanced to the NFL Championship game following their win, in their third try, over the Giants, George Young, Browns DE, was injured. Ford, mending from his injury two months earlier, noted Young’s condition and requested to play in the final. Coach Brown agreed, subject to the approval of the team doctor and plastic surgeon. Having had his jaw wired shut Lenny had dropped from 245 to 215 Lbs. on an all-liquid diet but had managed to return to 223, adding weight after having his wires removed. Lenny had been exercising at the local YMCA since his release from the hospital and deemed himself in playing shape. The doctors also agreed Ford could play, provided we wore a special mask, which was being prepared.

|

| Ford’s mask for the 1950 NFL Title game |

The 1950 NFL Title game opened in Cleveland’s sloppy, snow-covered Municipal Stadium with the visiting Los Angeles Rams going for an 82-yard touchdown pass in the opening seconds of the game, immediately putting the Browns on their heels. In early action it was Jim Martin at right defensive end with George Young at left defensive end, playing through injured ribs. But, entering late in the first half, Ford played excellently at defensive right end for essentially the entire rest of the game. Incredibly, considering the circumstances, he registered a long-stuff, a long-sack and consistently pressured Rams QBs as a mainstay in the Ram backfield. In the end of a thriller, the Browns could call themselves NFL Champions in their inaugural season as part of the combined league, an incredible accomplishment. Paul Brown would say that Ford proved he was a man that day.

1950 was also an interesting year for Ford’s former teammate and lifelong friend Bob Mann. Having led the NFL in receiving yards in 1949, Mann was asked by the Lions to take a pay cut during the offseason. Refusing, Mann held out and was then dealt to the New York Yankees for Bobby Layne. Mann arrived in New York to be told by Coach Red Strader that he had no idea why the trade was made, and that it was dreamed up and consummated by “the brass.” After participating in one series of an exhibition game between the Yanks and the Redskins, in which he caught a 50-yard touchdown, Mann was placed on waivers the next day, being told despite having already led the league in receiving – that at 170 pounds. – he was too light to play pro football. Finally, Mann was fired from his offseason job as a beer salesman with the National Beer Company which was, coincidentally, owned by Detroit Lions President Ed Anderson. Mann later claimed he was “blackballed” for his salary demands. Packer Coach Ronzani, in an address to a local Men’s club, denied that any team had been instructed to avoid Mann. Ronzani even said they had been in contact with him about a signing, but Mann was miffed and claimed he could make more money selling real estate than playing. Finally, in November of 1950, Mann would sign with the Packers where he remained through 1954 and the end of his career.

The offseason between 1950 and 1951 was also busy for the recovering Ford. Lenny was healthy enough in late January to be the newest member of the Browns 12-man basketball squad. This continued his hoops experience from high school and Morgan State. Ford had also been a practice participant in hoops at Michigan and as a semi-pro in prior off-seasons for the New York / Dayton Rens of the National Basketball League.

In his personal life, Ford followed Bob Mann in becoming a licensed real estate agent and purchased an investment property in his Detroit home. Ford got engaged to Geraldine Bledsoe a senior law school student from Wayne State University, who he had been dating since their days as undergrads at Michigan. Geraldine was introduced to Lenny by her father who was close with the football coaching staff at Morgan State. Upon Lenny’s moving to Michigan to play for the Wolverines, Geraldine’s father looked up Ford and introduced Lenny to his daughter. By June of that year the two wed in Plymouth Congregational Church in Pittsburgh, Pa. Geraldine, whose father was a practicing lawyer in the Detroit area, would go on to great personal success and provide Ford with two daughters Anita and Deborah before the two divorced in 1959. In May, Ford re-signed a contract extension with the Browns, the team fully confident they’d see the old Ford back in the Fall, in fact, they’d get much, much more.

This has been a great series so far. Can't wait to read what's next. Again great job Nick.

ReplyDelete