By Nick Webster

|

| Len Ford and Otto Graham |

Remaining at the Top

1952 was a great year for pass-rushers. The same season would see Norm Willey’s famous game in the Polo Grounds where he logged 15, er 13, er 11, er 8 sacks. Gino Marchetti (who would later join Ford on the first All-Time NFL Team) would jump onto the scene as a rookie for the ill-fated Dallas Texans and a young second-year Ram named Andy Robustelli would round into form. But sack counts aside – the numbers aren’t sufficiently complete to determine who definitively led the league in sacks in 1952 – the end the league was most concerned about was Len Ford.

The Browns opened 1952 avenging the championship loss against Los Angeles at home. Lenny, now wearing #80 as the NFL changed its uniform number guidelines after the 1951 season, had a relatively quiet day on the pass rush. However, for the second time, Lenny was dismissed from a game, this one certainly better deserved than the 1950 booting, after a fourth-quarter fight with Bill Lange. Ford exclaimed, “He’d been annoying me all afternoon and I couldn’t take it any longer”. Sounding like a player who deserved to be tossed. Though one must consider that Lange’s collegiate career ended in 1950 when he was tossed from his Dayton game against Chattanooga on Thanksgiving Day for slugging an official; this wasn’t a matchup of two choir boys. Controversy always swirled around these incidents of Ford’s. Lange later claimed that Ford was confused and that he’d only entered the game three plays earlier.

There is no film of the Rams tilt to open the year, but we do know that in the weeks following Lenny went on a tear notching sacks in seven consecutive games from Week 2 at Pittsburgh to Week 8 at home versus the Steelers. Ford topped out with 3.5 of the team’s seven sacks in the October 26 home matchup with the Redskins. Ford’s mercurial personality came out in that ‘Skins tilt, having bloodied little Redskin QB Eddie LeBaron’s nose Lenny was purported to have gently picked LeBaron off the ground and beg, “I’m awfully sorry, but I hope you understand that I’m just doing my job.” October 26 was also the day where the Eagles and Norm Willey tore into Giant QBs in the Polo Grounds and the traveling Dallas Texans, with rookie Gino Marchetti leading the charge, nailed 49er Y.A. Tittle for 95 yards lost and likely 10 sacks. Were records complete, it might have been the greatest pass rush weekend in NFL history. Ford followed the 3.5 sack Redskin game with a 2.5 sack road game against Bobby Layne and the Detroit Lions.

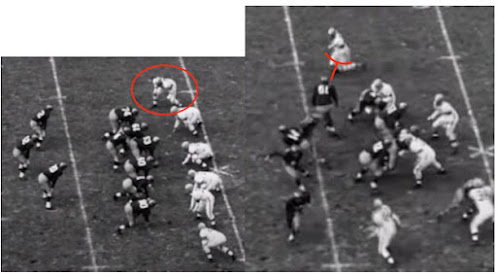

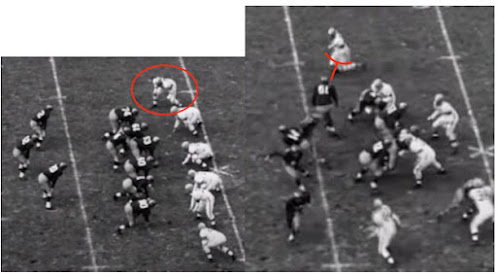

|

| Ford is still the ‘sprung-coil’, the Skins try to block him with the ‘flaring guard’ strategy here Gene Pepper |

Ford had at least 14 sacks in the 12-game 1952 season as the Browns again won their division but disappointingly lost the Championship game to the team who would be their new nemesis, the Detroit Lions. The 14 sacks are the most any player is known to have had in 1952, though depending on what you believe about Norm Willey, Gino Marchetti, or Andy Robustelli he might have been eclipsed. We do know that to that point in the season on October 26 Willey had been used sparingly at end and likely picked up his first sacks of the season in that Week 5 game. Robustelli had 10.5 known sacks in ’52 though if you assign the Rams’ 16 missing sacks pro-rata he’d land with 16 (the same approach for Ford and the Browns – with only five sacks missing – would land him on 15.5). Marchetti is a difficult case as so little exists on the nomadic Dallas Texans. He had three sacks in a spectacular debut at home against the Giants, could they block any quality pass rushers in 1952, and had 6.5 known sacks though the Texans had 30 missing sacks on the season including eight missing from that game at San Francisco where Gino had 1.5 of the two sacks accounted for. We may never know for certain who led the NFL in sacks in 1952, but we know for certain that Ford was among the leaders and most well regarded.

At season’s end Ford was again the only consensus First-team All-Pro end with Pete Pihos and

Larry Brink sharing honors among

AP, UPI, and

New York Post. However, if it were voted on today, Night Train Lane and his historic 14 interceptions would win Defensive Player of the Year. But in that era players were required to establish themselves prior to receiving high honors and, in fact, Lane only received honorable mention as defensive halfback with five different players receiving some First-team honors, including Lane’s teammate Herb Rich. Given that only middle guard Stan West and defensive tackles Arnie Weinmeister and Thurman McGraw were also consensus first teamers you’d have to consider that Ford would receive votes and possibly win a 1952 Defensive Player of the Year.

The Browns would lose the 1952 Title to the Detroit Lions who would – over the course of the next few years – battle back and forth with the Browns for Team of the Decade Honors.

|

| Doug Atkins (83) |

In January 1953, again at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia, the Browns selected another future Hall of Fame defensive end,

Doug Atkins of Tennessee. Atkins came out of Tennessee at 6’8” 240 pounds. with a pedigree as both a Football and Basketball star, perhaps Paul Brown thought he was getting Len Ford 2.0. Atkins was a 1952 All-American at defensive tackle and despite a very disappointing performance in the Vols Bowl Game against Texas, he was tabbed as a top end in the draft, in part because his height would disqualify him from eligibility from the Military Draft. Offseason speculation would swirl around exactly what the Browns rotation would be at end, though the general expectation was that Ford would continue at right end with Atkins stepping in for George Young at left end.

Ford suffered nicks and bumps during the preseason and wasn’t 100% going into the ’53 season with nagging foot injuries. In the opener in Milwaukee County Stadium against the Packers, Ford and Atkins did start at right and left end, respectively, with a healthy dose of George Young spelling the ailing Vet and the Rookie. Lenny and Doug showed very little and didn’t post a sack against a Packer team whose pass protection was far from the best in the league. The following week, however, Ford showed he was still at the top of his game posting three sacks for 11, nine, and 10-yards. There is unfortunately little published about the Week 4 contest against the Eagles, a game in which Lenny and Don Colo are known to have split a 12-yard sack, which unfortunately leaves 51 yards of sacks (likely five sacks) unaccounted for by the Browns. This is an outing where accounts indicate Lenny had a great game, the Pittsburgh Courier saying he was “ranging all over the field, breaking up plays before they started, and bringing down ball carriers with vicious tackles. Ford participated in at least 60 percent of the Browns tackles during the contest”- certainly an exaggeration, but the point remains.

Ford registered two, one, and one sacks in weeks 4 – 6 to complete a five-game stretch with at least 7.5 sacks, and likely more. However, Lenny would go sackless for the three games that followed and Atkins (who missed weeks 4 – 6 with injury) was slow to work his way up to expectations. The Browns defense performs well as a whole, however, first in points allowed leading them to an 11 – 1 record, though the line play is slightly off with Ford posting 10.5 known sacks (probably a couple more, particularly in the Eagle game) but with Atkins not playing up to George Young’s prior level, and with Bill Willis at 32 finally showing his age, posting just one sack after 11.5 and eight in each of the previous two seasons.

In 1954, both the league as a whole and the Browns were in the process of shifting to a four-man line. While many squads accomplished this by dropping the conventional Nose guard into what would become the middle linebacker position Willis sometimes drops, but sometimes stays on the line in four-man fronts, typically as the right defensive tackle. In later years, Blanton Collier would say part of their motivation in going to the four-man line was to get Ford closer to the passer; this is likely apocryphal; the entire league was moving in the same direction and Lenny’s most devastating play was from a five-man line. But Ford was still the physical freak that scared teams in 1953, it would become lore decades later that his running-mate Atkins was a freak who hurdled blockers. In fact, in 1953 it was Ford who could still leap tall buildings in a single bound and from whom Atkins was learning. Lenny still did things nobody else could. Not much is made of Ford grooming and bringing Atkins along, yet in 1953 Ford is primarily a stand-up DE, even when they go to a four-man line and Atkins – possibly a function of having been primarily a tackle in college – plays with his fist in the dirt.

|

| Nov first, 1953 Against Washington, Ford blows by the tackle trying to block him |

|

| Approaching the oncoming help from the RB, Ford leaps |

|

| Hurdling, landing and hitting the passer causing an errant throw |

|

| Doug Atkins, now with the Bears, shows what he learned from Lenny leaping over a blocker in this 1957 clip |

Following the 1953 season, Ford is again the lone consensus All-Pro at defensive end with Robustelli and Norm Willey each splitting First-team slots in two of the four primary teams. Gene Brito probably doesn’t get the awards attention he deserved in his first year fully focusing on defense. At this point, it’s clearly Ford, Robustelli, Willey, and Brito who are at the top of the game. Film study shows, however, that while Brito is extraordinarily effective, he is a different “finesse style” defensive end, using speed and agility but rarely power, to make plays in the backfield, and he cannot hold the edge against the run like Lenny. A Defensive Player of the Year probably goes to a defensive back with Jack Christensen of the Lions or Tom Keane (part of the same AAFC dispersal draft as Lenny) of the Colts would be likely leading the tally, though again, Lenny would be on the list.

In the post-season the Browns are again disappointed in the championship game by Christensen’s – really Bobby Layne’s – Detroit Lions, a second straight disappointment in a Title game, this time by a single point.

As the 1954 season approached, Ford began experiencing some minor injury problems typical of a defender accumulating wear and tear. Just as problematic, Atkins was not developing at the left end as Paul Brown would hope and the Brownies headed into their first season without Bill Willis, now retired, in the interior. As a team, however, the Browns’ D finished first in the league in points allowed for the third time in their five years in the NFL, finishing second in each of the other years; but they were doing it differently.

Through three weeks the Browns as a team totaled just two sacks, and Ford had no confirmed sacks, though one of the two sacks is unidentified. Following the third game at Pittsburgh Paul Brown replaced Doug Atkins with the diminutive end Carleton Massey, a rookie from Texas. On the right side Ford was called out as performing, “below par.” According to the Plain Dealer he, “didn’t seem to have his customary zip during the practice schedule. However, that was attributed to the fact that many of the experienced gridders use the exhibition for conditioning, so they’ll be ready when the bell rings. The bell tolled a month ago and Lenny still isn’t operating at anything near his usual efficiency.” The change to Massey at left end jarred something as the Browns netted three sacks in the fourth game, more than in the season to date, with the Plain Dealer noting that the “line looked better than it has all season with ends Carlton Massey . . . and Len Ford giving Lamar McHan a bad afternoon.” By November Ford, along with Massey, was operating “as well as ever,” probably having shed some extra offseason weight. Against the Giants at the Polo Grounds, Ford notched two sacks and teamed with Walt Michaels to knock Charlie Conerly out of the game. Ford and Massey both constantly pressured the passer and Paul Brown praised the D-Line.

The following Week, the tenth of the regular season, Len Ford missed the Browns charter flight to D.C. on Saturday, the day before the game. Knowing what would come later in his career and life, one wonders if the offseason weight gain coupled with this transgression were the first cracks beginning to show as Lenny was perhaps starting to let his personal issues with alcohol and self-control affect his play. Ford did make it to D.C. and the Browns won the matchup clinching a share of the title, but the D-Line didn’t log a sack. However, Lenny was constantly double-teamed and drew an intentional grounding penalty with the papers noting that he turned in, “his usual strong game”.

To the eye, Lenny is taking more plays off and not chasing plays away with the same vigor as in prior seasons. He’s not as solid in holding the edge against the run as in ’51 – ’53, but he constantly attracts double-teams and is still exceptionally effective when motivated. By season’s end, Lenny had regained his form after an admittedly slow start. Ford is named team MVP and is consensus First-team All-Pro for the fourth consecutive season alongside his first consensus running mate with Eagle end Norm Willey picking up those honors. Lenny is still considered a top – or top two – end in the league with Gene Brito off playing his trade in Canada for a season and Gino Marchetti in just his second season at DE after experimenting on the offensive Line in 1953.

The Browns end 1954 on a high note finally taking the Championship back from the Lions after losing in each of the previous two Title games to Bobby Layne’s team. The Browns trounce the Lions 56 – 16, and Lenny nabs two of the six Browns interceptions. In the Pro Bowl in early January, Lenny again shows up big, with the East defense powering the first two TDs.

Nick, thanks for the extraordinary (and extraordinarily detailed) series on Len Ford....it's so great to read this level of detail on a legend that few if any of us have seen in any detail (and certainly a tiny number who remember him contemporarily).....I have noted in my limited viewing how enamored I am with Bill Willis....in your highly knowledgeable view, what as you see it might be the cause/effect or relationship of Willis's disruption and Ford's effectiveness (or vice versa or something else?) thanks in advance....

ReplyDeleteOh they certainly play off one another. As I noted, Willis' sacks were of his own making, not Ford flushing passers his way, Ford does benefit from a few where the passer is totally disrupted by Willis. Honestly - on film - 1951 Willis looks like recent Aaron Donald or peak Joe Greene and Alan Page, he's SO quick that at full speed he just shows up in the backfield where he doesn't belong. Whatever you think about Lilly and Olsen (they're great) but that's not the way they did it. Only Willis, Page, Greene and Donald had that ability to immediately penetrate into the interior - they are the four who most frequently appear as if they will actually take the handoff rather than the runner.

ReplyDelete