By Joe Zagorski

Pro football games are typically won thanks primarily to a strong offense or a stalwart defense. The efforts of the players usually dictate which of these two entities will have the edge in determining winners and losers. Sometimes the possibility of luck sneaks in, however, and gets a say in how a winning team emerges in a contest. On January 1, 1978, that is exactly what happened…in a big way, and in a very big game.

The AFC Championship Game on that day pitted the defending Super Bowl Champion Oakland Raiders versus the Cinderella team of the 1977 NFL season, the Denver Broncos. The site was Mile High Stadium in Denver, where the Broncos had owned what could be considered a very strong home-field advantage. But what determined the winner of this game was not the venue where it was held. Nor was the game decided by either team’s offense or defense. Rather, it was a quick decision by the officials, and in particular head linesman Ed Marion, which in the end produced a win for the Broncos. The play in that game that resulted in that contest’s eventual result would become known as the Rob Lytle Non-Fumble, and it was perhaps the most controversial play in conference championship game history.

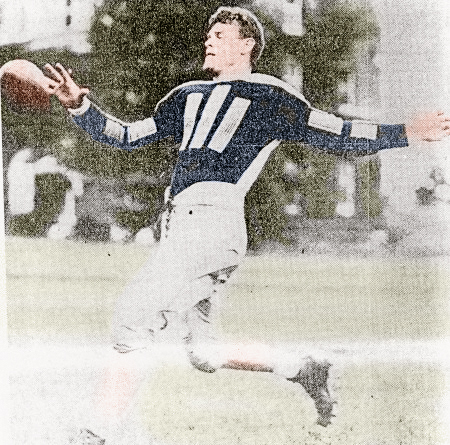

The scene was about midway through the third quarter. Denver was holding on to a slim 7-3 lead, but they were driving deep into Oakland territory. The Broncos offense was situated with a first-and-goal position from the Raiders’ 2-yard line. That set the stage for a quick dive run by rookie Broncos running back Rob Lytle. But just before the combatants took their stances at the line of scrimmage for that play, a veteran Oakland defensive lineman managed to overhear something.

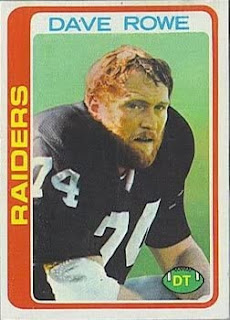

“I remember that game like it was yesterday,” said Raiders nose tackle Dave Rowe. “I’ll walk you through the play. I’m standing there, and you know, when you’re a defensive lineman, you’re standing there right by the ball. Well, I look across at the (Denver) huddle, and I hear their quarterback (Craig Morton) say ’30 Power,’ or something like that. And I turned around, and I’m looking as we huddle up…I turned around and I looked at (Oakland safety) Jack Tatum and I said, ‘Tate! I heard the play. They’re coming right up the middle.’ He looks at me and he goes, ‘Are you sure?’ I said, ‘I heard the play! I heard it!’ I mean the play being called is what you don’t really usually hear. Their crowd was quiet, because they had the ball. That’s why I probably could hear it.”

Tatum now had an idea as to what he could do on the upcoming play. No one knows what his actual duty would have been on that play, but being that he was Jack Tatum, arguably the hardest hitman in pro football history from the safety position…well, you could almost guess what he was going to do. He took Rowe’s affirmation to heart. He was going to run up to the line of scrimmage at full speed and torpedo the play.

Dave Rowe had a defined task on the play as well. He knew that on any power running play near the goal line, the lineman—whether it be an offensive lineman or a defensive lineman—who exudes the most strength, is generally the one who is able to help his team out the most in achieving success on that particular type of play.

“So you’re a defensive lineman,” continued Rowe, “and all you’re doing is just plowing straight ahead, trying to get penetration. Tatum came up and stuffed him (Lytle). Oh man! He stuffed him! Oh it was a heck of a hit. And that ball…he (Lytle) was up in the air. It was almost like he looked like he was trying to jump over (the pile of bodies). And he got struck, and that ball fell…it had to fall three feet down.”

Rowe got down low enough to give Tatum a clear shot at Lytle, who came to an abrupt stop, thanks to Tatum’s influential hit. No less than a half-dozen players tried to find the pigskin, and then pry it out of the pileup of bodies around the line of scrimmage. Veteran Raiders defensive end Mike McCoy was the man who stood up with the football and began running with it downfield toward Denver’s end zone. Enter the controversy.

“Mike McCoy picks the ball up and takes off,” recalled Rowe. “He’s got like a 25-yard lead on anybody! All of a sudden, they (the referees) are blowing whistles. It’s like what?!? They (the referees) say ‘No, he (Lytle) was down.’ And we’re sitting there going ‘He wasn’t down! He wasn’t even close to being down!’ Why they called him down I’ll never know.”

The official verdict came from head linesman Ed Marion, who declared that the runner’s forward progress was stopped. For sure, after Tatum hit Lytle, forward progress was definitely stopped. But when that happened, and when the ball fell to the ground, the officials should have blown their whistles, declaring the play to be over. That did not happen. If you watch the NBC-TV broadcast, no whistle is heard until well after McCoy begins his sprint downfield.

“I think what happened was…I think that one referee made the call, and nobody else (on the officiating crew) wanted to overrule him,” explained Rowe. “They didn’t do a little conference or anything. They just said ‘Nope…he was down.’ And it was so blatant. Of course, that turned the game around.”

As Lytle was being helped by Denver’s trainers to return to the sideline, the Raiders players on the field disagreed with Marion’s decision in a rather vehement fashion. So much so, in fact, that the officials threw a flag on Oakland for “Unsportsmanlike Conduct.” That placed the ball at the 1-yard line. The very next play, Denver running back Jon Keyworth took a pitchout from Morton and just made it into the corner of the Raiders end zone.

Keyworth’s touchdown boosted the Broncos to a 14-3 advantage. They would hold on to prevail, 20-17, thus giving them their very first conference championship and a ticket to Super Bowl XII. But all that anyone on the Raiders was concerned about was the fumble by Rob Lytle that was declared by the referees to be a non-fumble.

“Oh, we were screaming at the referees,” said Rowe in the immediate aftermath of that play near the goal line. “Everybody was screaming. Everybody was saying ‘It’s so clear!’ And I guess that he (Ed Marion) just didn’t want to see it. I don’t know if there was profanity thrown out there or not. But I just remember that everybody was screaming. Well, then we got penalized, and they go in and score.”

Being angry at the officials is part and parcel of anybody’s psyche who experiences a questionable call getting leveled at their team, especially if that call prevents them from going to a Super Bowl. If you take away Keyworth’s score, as McCoy’s fumble recovery would have done, then the Raiders would have probably claimed victory over the Broncos. The Oakland players and fans both then and now believe that to be true, and they still get upset when discussing the 1977 AFC Title Game. Everyone with an open mind who saw Tatum’s hit and Lytle’s fumble will resolutely claim that Oakland got ripped off by the referees. And no less a person than Oakland’s managing general partner Al Davis felt the same way.

“We go in the locker room after the game,” said Rowe, “and I remember hearing Al Davis in a conversation with three or four other players. He turned around and these are his words…he said, ‘That will never happen again…because we’re going to have instant replay.’ And I mean I’m like, ‘Wow!’ You know I never thought about instant replay, but that’s what he said. He said ‘That will never happen again. We need instant replay.’”

It would take until 1986 until an Instant Replay system was installed in the NFL for regular season and postseason games. And there would be several more egregious calls—and non-calls—by officials in several more big games, which would occur before teams and coaches could challenge plays on the field with the use of an Instant Replay system. But no one who was there or who watched it on television will ever forget the epic Rob Lytle fumble—or non-fumble—in the 1977 AFC Championship Game.

“It was the most blatant miss that I’ve ever seen in football,” lamented Rowe. “I’ve seen a lot of instances. You’ve got those things where you ask ‘Was he down? Was he up? Was his knee down? Was his knee up? Was it a quarter of an inch off the ground?’ I can understand that. But this was the most terrible call in all of football. It was the worst ever. I mean to take and to have the whole game decided by one play, and then have the referees be the arbiter of it. We always used to have a statement: ‘Don’t allow the referees to decide the game.’ And they did. They controlled that game, because that whole game turned around, and we missed out of going to the Super Bowl. And I believe that we would have beaten Dallas in Super Bowl XII.”

Rowe can be excused for being upset, even 45 years after the event. Getting to a Super Bowl takes a lot of hard work and sacrifice. Then to see your chance to go to the biggest game of the year denied by a missed call by a referee…well, that has to be most upsetting. You would have at least thought that the official closest to the runner would have blown the play dead. That is what they are supposed to do.

“There was no whistle,” continued Rowe. “I didn’t hear a whistle. And I’m right there in the middle of all of it. I’m right over on top of the left guard and the left shoulder of the center. If there had been a whistle, or somebody running in with a whistle…but I mean, it wasn’t like he (Lytle) was even close to being down. He was up in the air, and the ball came straight down! I mean it was right there! I thought that one referee (Marion) made the call, and the others didn’t want to overrule him. Well maybe I didn’t see it, but they all saw it. They had to see it. On film…it’s really plain on film! Well, it wasn’t even close. That’s the thing. Referees are human. I understand that. But he had to see it! He could not have not seen that.”

Fortunately for the good of the game, however, enough influential people did see the Rob Lytle non-fumble to spend time discussing it when they talked about the possibility of installing an instant replay system in the league’s annual competition committee meetings. Even with the modern technology used today, mistakes are still being made, and will continue to be made with the instant replay system. Nevertheless, a vital chapter that moved the debate towards reducing mistakes on the field with the possibility of utilizing instant replay occurred on the field at Denver’s Mile High Stadium on January 1, 1978, when the Broncos beat the Raiders, thanks in large part to Rob Lytle’s Non-Fumble.

Sources Used:

Interview with Dave Rowe on October 26, 2021.

Reidenbaugh, Lowell and Attner, Paul. The Sporting News Super Bowl Book. St. Louis: The

Sporting News, 1987.

Joe Zagorski is a member of the Pro Football Writers of America and the Pro Football Researchers Association. He has written five previous pro football-themed books, and he is currently working on three more pro football-themed books. In 2021, he was bestowed with the Pro Football Researchers Association’s Ralph Hay Award for lifetime achievement in pro football research and historiography. He lives in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.