Every so often, you can go back and see things in football history that make you scratch your head. It may be a player who was overlooked for the Hall of Fame ... something that contradicted conventional wisdom ... or a coach who deployed players in an extraordinary manner.

Which brings us to today's story.

In the era of the 4-3 defense -- call it the mid-1950s through the 1970s -- there were accepted philosophies involving who lined up at particular positions. A strong safety, for instance, usually played on the tight-end side ... with the free safety away. Or a cornerback who was better at run support lined up on the left side of the defense because opponents game-planned runs in that direction.

Then there was the left defensive end. He generally was the better all-around player, a bit bigger and maybe stronger than the defensive right end who was smaller and sometimes quicker. The same theory that applied to cornerbacks was practiced here, mostly because opponents ran more to their right (and the defense's left).

Of course, there were exceptions, and the defensive bookends of 1976-77 Kansas City Chiefs were one of the most notable.

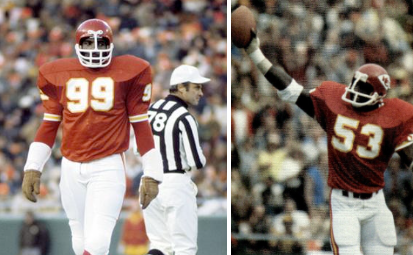

Not only did they position the bigger player on the right end and the quicker player on the left, but look at the disparity between the two: Their strong-side end was listed as 6-foot-3 and 220 pounds; their right-side defensive end was 6-6 and 285 pounds.

That made the left end the smallest in the NFL, and the right defensive end the biggest ... and they were on the wrong sides!

On the right was Wilbur Young, who was actually larger than the listed 285 pounds. He was probably 300 pounds or more. He'd been a right defensive end for a few years and had a good season there in 1975, with 12-1/2 sacks, according to Chiefs' records.

Whitney Paul was the left end in question. He was a rookie in 1976, a 10th-round pick out of the University of Colorado who, by midseason, was the starting defensive end on the strong side of the Chiefs' defensive line. By that time, his weight was closer to 233 pounds, but he was still light for the position. And though Young was heavier, both looked out of place.

So what to do? That was up to Chiefs' coach, Paul Wiggin, a former Pro Bowl left defensive end and one of the game's best defensive line coaches. And he was stuck.

He didn't have a plan. He had a problem.

Initially, the idea in 1976 was to be the same as 1975 -- with Young as the right defensive end and the huge (6-foot-8, 280-pound) John Matuszak on the left. But Matuszak's behavior early that season was more erratic than usual, and his antics forced the Chiefs to trade him to Washington prior to the regular season.

The problems had nothing to do with Matuszak's play on the field and everything to do with his behavior off of it. One Friday night in August, Wiggin found him unresponsive in the locker room with his girlfriend (who tried to run "the Tooz" over in a previous incident) after she said he'd consumed pills and alcohol -- specifically, vodka and Valium.

Wiggin acted quickly, rushing the unresponsive Matuszak to a nearby hospital where he was treated for an overdose, and his life was saved. Sadly, Matuszak never learned his lesson. After he was released by Washington, he went on to Oakland and won two Super Bowl rings. But he died from an accidental overdose in 1989 at the age of 38.

Matuszak's exit in 1976 left Wiggin in a pickle. He was short a talented (albeit out-of-control) left defensive end with few viable options. So he positioned the rookie, Whitney Paul, at left end - creating a sort-of "Mutt-and-Jeff" situation with Young, caused by the departure of "the Tooz."

The result? Not good.

Wiggin gained little production from his ends in either the pass rush or run game. In 1976 Paul had 3-1/2 sacks and Young just 1-1/2, according to official gamebooks -- the lowest total of any pair of starting defensive ends in the NFL. The following year, Young totaled 5-1/2, and Paul had another 3-1/2 sacks -- improvement, yes, but not enough to place them out of the NFL's bottom five for a tandem of defensive-end starters.

But that wasn't all. The Chiefs' defensive unit as a whole wasn't stopping anyone from running on it, either -- both seasons ranking last in the NFL in most run-stopping statistics.

Enough was enough, and, Wiggin was fired on Halloween, 1977. The "patience" he said he was promised ended early, and he was dismissed in favor of a new coach -- Hall-of-Famer Marv Levy -- who introduced a new defensive philosophy by switching to a 3-4 defense.

Levy's first priority was fixing his defensive ends, and he wasted no time doing it. The Chiefs took defensive end Art Still with the second overall pick of the 1978 draft and Sylvester Hicks, another defensive end, with the 29th overall choice).

Both were starters as rookies.

Not satisfied, the Chiefs drafted yet another defensive end, Mike Bell out of Colorado State, with the second overall pick in 1979 -- a testament to how serious Kansas City was about upgrading the position.

As for Paul and Young, their stories didn't end there. They had just been put in a tough position, and, yes, I mean that literally. Young wound up with the Chargers, backing up defensive tackles Louis Kelcher and Gary Johnson. But when Kelcher was sidelined by a knee injury in 1979, it was Young who stepped in and had such an outstanding season, with 14 sacks and All-AFC honors, that the late Paul Zimmerman named him one of his All-Pro defensive tackles.

"The Chargers' gigantic Wilbur Young," Zimmerman wrote, "moved inside for the injured Louie Kelcher and found a home. He became a freewheeling, offense-shattering tackle in the best Leo Nomellini tradition."

He wasn't the only one to find success. Under Levy, Whitney Paul was moved to a position more suited to his size -- outside linebacker in a 3-4 defense -- and there he found a home. He had three interceptions and four sacks in 1978 and eight sacks one year later.

In each season, he scored a defensive touchdown.

Later traded to New Orleans, Paul excelled under coach Bum Phillips and his son, defensive coach Wade Phillips. Playing the opposite edge to Hall-of-Famer Rickey Jackson, Paul averaged six sacks in four years -- including one 9-1/2-sack season. Ironically, both he and Young found success in positions more suited to their body types than where they lined up in 1976-77. The big man, Young, ended his career playing interior defensive line, while the small guy, Paul, was moved to linebacker.

Is there a lesson there?

Perhaps. After all, there was logic to axioms involving the size of players at particular positions -- at least, there was here. Paul and Young were victims of circumstances beyond their control and could've been considered failures.

Except they weren't. Both went on to credible careers, and while they won't qualify for any Hall of Very Good, they are worth remembering for what they did ... and did not ... do.

No comments:

Post a Comment