By Nick Webster

|

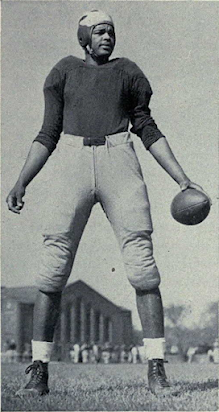

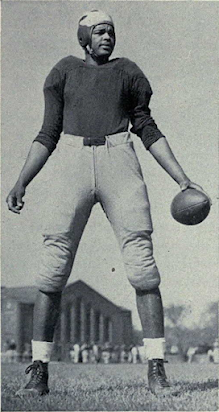

| Len Ford at Michigan |

This long piece is dedicated to T.J. Troup who taught me that ‘the tape never lies’ and Chris Willis who provided so much support in its creation.

Here at The Journal, we enjoy diving deep on some of the best accomplishments, best seasons, and best players in NFL history. We all know about some of the great recent pass-rush seasons JJ’s 2012, Strahan’s 2001, Reggie’s 1987, and with some of the work we’ve done, since published by Pro Football Reference, Bubba Baker’s 1978, and Deacon’s dominance of the mid-’60’s. 1950s pass rush data is even more sparse; however, we do know that some of the great pass rush seasons occurred during that decade, and we’ll dive deep on one of those today.

Given the permanent move to two-platoon football, the 50s was when pass-rushing became a unique skill. No longer was an end’s defensive play valued in the context of his pass-catching or run blocking; for a defensive end, his defensive play became THE only factor in his evaluation. Prior to the 50’s, there were great pass rushers like Bill Hewitt, Jack Zilly, Ed Sprinkle and the like, but these were players who did it all and just happened to excel on the defensive side of the ball rather than being dedicated defenders; save Sprinkler’s later years in the ’50s.

The first wave of great full-time pass rushers were Sprinkle, Andy Robustelli, Norm Willey, Gino Marchetti, and Len Ford. And the first two-platoon breakout pass-rush season was Len Ford’s 1951, which we’ll cover in detail while discussing Ford and his life overall.

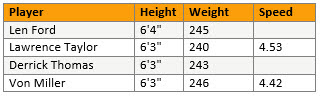

Len Ford was born to be a superstar pass rusher. He was tall and long, with size and speed, and would look like any star outside linebacker or defensive end/edge rusher in today’s game.

Watching peak Len Ford on film is like watching peak Lawrence Taylor, and frankly he is more disruptive than

Von Miller or

Derrick Thomas; he is faster than anyone his size and bigger than anyone his speed, he looks different. Slightly bow-legged, his wife would later say she could always spot him on the field bow-legged with his hand on his hip, he played like a coiled spring ready to pounce and was able to thrust his large frame at any time with devastating power. Blocking schemes of the day frequently had offensive tackles go straight at defensive tackles aligned over them (similar to a 3-4 DE alignment today) asking an offensive guard to ‘flare-out’ and block the onrushing five-man line DE (think of a ‘wide-9’ alignment today); these blocking schemes simply were not fit for Len Ford, and he would exploit them routinely, as we will see.

Early Years

Ford was born Leonard Guy Ford Jr. and raised in Washington D.C. the second child and first son born to Leonard G. and Jerlean Ford. Lenny, as his friends called him, was a three-sport letterman at Armstrong High School less than two miles from the White House in Washington D.C. Armstrong had a litany of famous alumni including Duke Ellington, Billy Eckstein, and, a decade or so later, Packer legend and fellow NFL Hall of Famer Willie Wood. Ford lettered in baseball, football, and basketball, but as his Hall of Fame Presenter and High School Football coach Ted McIntyre said he was a “(B)oy who dreamed of Football instead of Cowboys and Indians.” He was named All-City in football as a Junior and Senior at tackle and end. And was All-City in all three sports as a Senior. Ford wanted to play football at colleges highest level but was not provided financial assistance by Ohio State. Coach McIntyre suggested, given the options, that he should attend nearby Historically Black College Morgan State.

Ford spent a short stint at Morgan State in 1943 and 1944, where he played basketball as a frequent starter at forward and center, helping lead the ’43-’44 basketball team to a league title. Ford joined the football team for the Fall of 1944 in the midst of the teams’ glory years, and Lenny became a consistent starter at left end for the Bears. His coach Ed Hurt, had been leading the Bears since 1929 and would coach the team until 1959. During this run, they won Black National Titles in 1943 and 1944 and then again in 1946, after Lenny left. The 1944 Bears football team went 6-1 and did not give up a TD during the regular season. Their only loss was 2-0 to Tuskegee Air Base when a punt returner was downed for a safety. The only other score allowed was a field goal in their final game of the season at Virginia State. The Bears did fall to Grambling however in their early January bowl game. The coaching staff would be an integral part of Ford’s later life. Lenny left school for a brief stop in the Navy in 1945 as WWII was coming to an end. As the war concluded, and with his grandmothers’ blessing, Ford decided to leave the D.C. area to play at the highest level of competition. He applied for admission at five different Big-10 schools and received a single response, from the University of Michigan. For that 1945 season, Ford transferred to Michigan in hopes of one day playing in a Rose Bowl.

Michigan

Wearing number 84 in 1945 then 87 in 1946 and 1947, Ford was a star at Michigan but shared time at left end during the 1946 and 1947 seasons with lifelong friend, number 81,

Bob Mann, who was slightly built, fleet-footed, and a superior pass catcher, though less stout on defense. This rotation – for the time - largely featured Ford at left end on defense and Mann on offense, with Ford occasionally spelling Mann on the offensive side of the ball. Viewing the “games started” figures at Michigan is misleading given the way we think of the game today. In the ’46 and ’47 seasons, Ford would be considered the starting defensive end in all the games, but Mann was the starter on offense. In fact, Wolverines head coach, and Amos Alonzo Stagg disciple, Fritz Crisler would be known as the “Father of Two-Platoon Football.” A few years later in 1949 Mann’s receiving prowess was illustrated as he joined Mac Speedie and Tom Fears as the fourth, fifth, and sixth players to reach 1,000 receiving yards in a pro season. Ford was the tallest player on the Wolverines throughout his tenure entering the 1945 season at 6’5” but weighing only 190 pounds at the time, by 1946 Ford weighed in at 207 but was now listed at 6’4” (a modern combine measurement would likely list him at 6’4 ½), and he tipped the scales at 215 in 1947.

Where these figures differ from College Football Reference, they have been verified with University of Michigan Archives, e.g.: Ford’s 3 receptions in 1947, https://www.sports-reference.com/cfb/players/len-ford-1.html

Ford was used sparingly on offense in 1945 as Coach Crisler pursued the then novel strategy of rotating offensive and defensive lines, but he still produced enough on the defensive side of the ball to join five Wolverine teammates and receive honorable mention, Ford as an end, by United Press. Lenny didn’t even play in the first 4-games of the season but saw meaningful action beginning in the Army game and was a mainstay on defense thereafter. In the loss to the #1 ranked Army team with 70,000 at Yankee stadium in attendance, Ford was called the “center of all eyes . . . only because of his outstanding work at right end.” That Ford garnered such attention was meaningful given that the Wolverines were facing the most formidable team in the nation. Army would go undefeated for the second straight year and featured 1945 Heisman Trophy winner Doc Blanchard and future 1946 Heisman Trophy winner Glen Davis. But it was Ford, not Mr. Inside or Mr. Outside that caught the eye of the New York Times that day.

The following week at Illinois Ford had a breakout game with a forced fumble on a running play, three QB sacks for 23 Yards in losses, and his first career TD on a 15-yard blocked punt return, breaking open what was a 0-0 tie at the time. “Ford was devastating in his attack on the Illinois passing offense. He charged in relentlessly and downed the passer before he can flick the ball. The big, tall, powerful negro can’t be stopped by any one man and Illinois found that out.” The following week against Minnesota, “the lanky Ford delighted the crowd and received an ovation when he left the game for the last time.”

|

| Ford punches the ball away from a ballcarrier for a first-quater forced fumble at Illinois in 1945 |

|

| Ford comes in unblocked for a second-quarter sack of Illinois QB in 1945 |

Ford started the first three games of 1946 including the opener against Indiana the week two tilt against Iowa, and a loss against Army. Bob Mann would frequently sub-in before Ed McNeill supplanted him as starter in game 4 against Northwestern. Ford started again against Illinois but was used primarily on defense behind McNeill and Mann who started the remainder of the season. Ford did have the distinction of catching an extra-point pass after a blocked kick in the Wolverines rout of Michigan State.

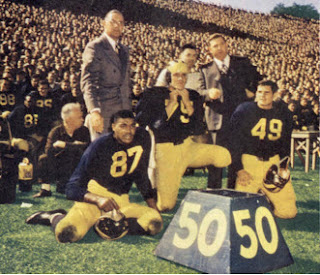

During the 1947 season, Mann started 8 games and was named Second-team All-American, but Ford was named Third-team All-American despite only starting just 1 game. Crisler continued the two-platoon of Ford on defense and Mann on offense. Ford played 231 minutes in the regular season and 32 in the Rose Bowl to Mann’s 207 and 25, respectively. Len scored a TD against Pittsburgh recovering his own teammate's fumble on an interception return and carrying it into the endzone. Lenny had another exemplary game against Indiana sacking their All-American quarterback candidate (and future Los Angeles Don teammate) George Taliaferro, knocking him out for a few critical games with bruised ribs and a shoulder separation. “Ford, labelled by some of the critics in the press box as the strongest defensive end they had ever seen, was a constant annoyance to the Hoosier attack.” He was singled out again for his spectacular play in the season-ending rivalry victory over Ohio State.

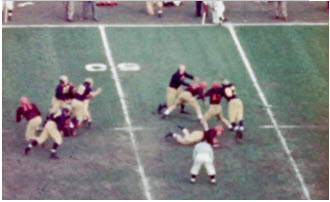

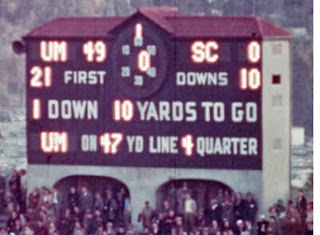

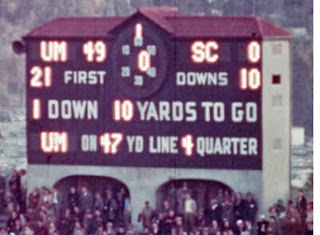

Following the regular season, the Wolverines were ranked #2 behind the top-ranked Notre Dame Fighting Irish. However, the Wolverines decisive 49-0 shutout Rose Bowl victory over #8 Southern Cal caused voters to reconsider, particularly given that the Irish had only beaten USC 38-7 earlier in December. In the nationally televised NBC game, Ford starred defensively, in on six tackles, had a shared 8-yard sack, and another sack-forced-fumble in the fourth quarter. Lenny also recovered a fumble on an Alvin Wistert (the brother of Albert of Eagles’ fame) sack forced fumble. On the offensive side of the ball, Lenny had two scampers on spinners for 16 and seven yards and a 12-yard reception. The 1947 season became one of the original disputed NCAA Titles, the AP – unusual for the time – issued a new post-Bowl Poll that ranked Michigan #1. All these years later, this is still disputed, and Notre Dame still declares their 1947 team as the National Champion.

|

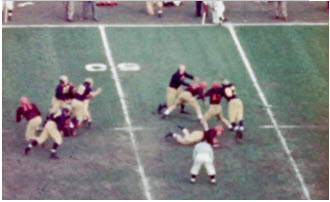

| [Ford closing in to share an 8-yard sack in the first Quarter of the Rose Bowl] |

|

| [Ford’s fourth Quarter Tomahawk sack forced fumble in the Rose Bowl] |

|

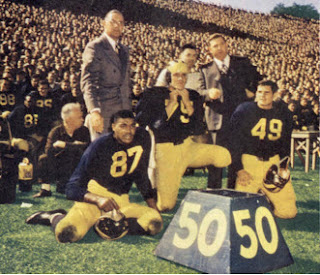

| Ford with Coach and Teammates on the sideline at the Rose Bowl] |

|

| [Final score in 1947 Rose Bowl between Michigan and USC] |

Michigan Coach Crisler’s strategy of rotating on offense and defense probably optimized team performance but may have limited Ford’s accolades. The Los Angeles Evening Citizen noted, “his big bid for mythical honors last fall was blocked by Fritz Crisler’s two-team system that utilized him on defense only.” Film study shows it wasn’t defense only, but by and large, the point holds.

What an absolute unit at his height and weight. Size and athleticism to play in any era.

ReplyDelete