Michael Dean's older brother, William "The Refrigerator" Perry, due to his size and charisma got far more attention than he did. Perry had size, charisma, and a coach who would play him as a fullback on occasion.

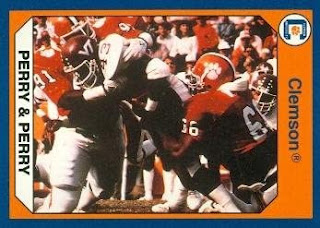

After being an All-American standout at Clemson University, Perry was drafted by the Cleveland Browns in the second round of the 1988 NFL Draft. Perry had an ankle issue in college, breaking his ankle as a sophomore causing him to miss significant time.

He recovered to set ACC record for career tackles for loss and sacks. It earned lots of accolades—First-team All-American selection in 1987, First-team All-ACC in 1986 and 1987. Additionally, he was ACC Player of the Year in 1987, not just the top defensive player, but the top player in the conference.

He spent his rookie season as a mostly nickel rusher and was an impact as a rookie, making all of the All-Rookie teams totaling six sacks and four run stuffs and forcing a pair of fumbles, recovering two (one for a touchdown).

It was a good start for the youngest of the Perry family's twelve children. Yes, twelve.

In camp, when he spelled starters but never got a starting position likely due to inexperience in the techniques he was asked but he whipped everyone in pass rush drills. The Browns were basically a 3-4 team at first and Perry played end in that base scheme, sometimes lining up very wide, wider than a usual end in a 30 front—he had enough speed to rush from the edge.

However, late in the season the Browns played a lot of the 46 Defense and Perry was a three-technique in that scheme, and that allowed him to do his thing—get into the backfield quickly.

In 1989 he took over as the starting right defensive tackle and he was even more dynamic. He was voted the AFC Defensive Player of the Year by UPI and the Kansas City Committee of 101 and was a consensus All-Pro.

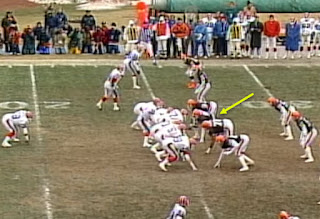

The right tackle position meant that he didn't "flop" sides depending on the strength of the offensive formation. He did that later in his career but not generally with the Browns. It meant that if the tight end were to the offense's right and the Browns wanted to shift that way, Perry was a nose tackle, slanted on the center. If they wanted to shift away he'd be a three-technique. He didn't get the opportunity to always play the three-technique like some of his contemporaries like Keith Millard and John Randle or later Warren Sapp or even current three-technique Aaron Donald.

|

| Perry in an overshift with Perry as a tilted nose tackle |

|

| Perry is a three-technique here, on the outside shoulder of the left guard |

Still, Perry's forte was getting into the backfield and tackling runners for losses and in 1989 he totaled 11.5 stuffs and seven sacks and batted away seven passes. According to PFJ's Nick Webster, his stuff total was good for third in the NFL.

In 1990 he was again consensus All-Pro and had a remarkable 11.5 stuffs and 11.5 sacks, a total of 23 plays behind the line of scrimmage while totaling a career-high 86 tackles. For younger fans, these are Aaron Donald-type numbers.

That year he did get the benefit of switching sides to be in the most favorable of positions on any given play because Chris Pike, a 6-8, 280-pound tackle, emerged as a solid shade tackle allowed for the change.

His rare quickness. Said Perry, "Quickness is my best asset, it is not something you learn. It's God-given." For an interior defensive lineman and great anticipation allowed him to penetrate the line of scrimmage and make plays that most defensive tackles couldn't.

After one game in 1990 his coach Bud Carson said, "He's reached another dimension."

His quickness caused him to get plenty of double teams as well—

|

| Dean getting doubled, with the guard going high and the tackle going low |

In 1991 Perry held out, wanting a raise from his rookie contract, but with the hiring of Bill Belichick

and the team stepped forward and in a new scheme Dean again played well.

Billichick's new scheme, was more a run-stopping defense, though not the 3-4 he ran in New York. It required more gap discipline and didn't allow Perry the freedom to penetrate as he had in Carson's one-gap scheme. He couldn't just attack as he'd been allowed to under Carson.

However, the Belichick scheme didn't limit him in terms of his production which is remarkable given the required techniques he was asked to employ. In 1991 he had 10.5 stuffs tied for sixth in the NFL according to Webster. His stuff total dipped in 1992 (has knee surgery in August) but in 1993 he had a career-high of 14.0 stuffs, good for third in the NFL.

However, he was never able to get double-digit sacks again, like he did in 1990. Said Perry, "anyone—offensive or defensively—wants to play in a scheme where they are used properly. Don't take away my attributes, that is getting off the ball penetrating causing chaos and making plays." Perry felt the base defense techniques he had to play limited his ability to rush the passer if teams happened to pass in likely run situations.

There were some exceptions, however. In 1993 the Browns signed Jerry Ball to play nose tackle and the next year young Bill Johnson took over the nose when Ball left (he signed with the Raiders as a free agent).

So, then with those two playing the nose tackle spot, Perry got to play three-technique almost all the time for the first time since 1990 because they would "flop" based on the offensive formation putting him in a position to not be double-teamed as much and in an ideal spot to rush the passer. Essentially the Browns coaches allowed Perry more freedom and less of the two-gapping they required in the first couple of seasons they were there, this was something Perry had not been able to enjoy since 1990.

Previously he played both three-technique and nose tackle, the tackles did not switch sides they shifted left or right based on the offensive formation, and when he was shaded (in the shoulder of the center, not head up) over the center it put him in a poor position to get after the quarterback on perhaps half the downs of a game. He wanted to penetrate every time so with this new "flop-the-tackles" strategy he was able to do that.

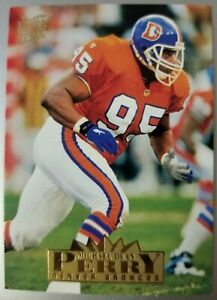

Despite those changes, the Browns and Perry's marriage ended in 1995 when Perry signed with the Broncos. Perry was unprotected and unclaimed in the 1995 expansion draft he became a Browns' cap casualty being cut but Cleveland. He subsequently signed with the Broncos signed a three-year $7.2 million with Denver—a move that took him off the expansion list. The details of that are hard to track down but the papers mentioned that it occurred.

There he finally played the three-technique full-time, always on the outside of the guard, not playing there sometimes and over the center sometimes—it was likely his natural position. He responded with a good season with 8.5 stuffs and 6 sacks and was voted Second-team All-AFC by UPI voters.

With the addition of power rusher Jumpy Geathers in 1996 Perry would usually play his preferred position of three-tech in the base defense but would usually play shade/one-tech on the shoulder of the center on passing downs.

It was a move to get the best interior rushers on the field at the same time and Geathers, who only played in passing situations, was just devasting on guards with his forklift move so Perry, unselfishly, would play on the center to allow Geathers to do what he did best.

Certainly, there was more to it in the Broncos nickel schemes but that is a story for a different day. That year Perry made his seventh and final Pro Bowl and was second-team All-AFC again.

Late in 1997, it seems Perry ran out of gas. In December the Broncos cut him due to his health problems and also his lack of production. Perry's knees were bothersome more in 1997 than in the past. He was inactive for a good stretch of the season and that frustrated Perry.

He eventually told the team he didn't want to remain a Bronco if he wasn't active on game day. So, really, Perry cut himself. A few days later the Chiefs signed him to fill in at the end of the season but he did not play much. He played in just one game and made one tackle with the Chiefs and didn't play in the playoff matchup with the Broncos.

Film study shows a short, low center-of-gravity guy with tremendous quickness—among the quickest off-the-ball we've ever seen. He was able to get his body in front of a center or guard on the play side and if those guys tried to get a quick jump into the hole, Perry would just "backdoor it", getting behind the linemen and making a tackle for loss from the backside.

Still, Perry has never gotten any Hall of Fame traction and this is Perry's last season to make the modern list if he does not make the Hall this year he will fall into the senior's abyss (so-called because there are so many players there and only one per year makes it out).

In his career, he was All-Pro five times (two consensus) and received post-season honors in eight of his ten seasons, including Pro Bowls and All-AFC selections.

In his seven-year peak (1989-95), Perry averaged 10½ stuffs and 7½ sacks for 18 plays for losses. Trust us, those are great numbers for such a long span.

We don't expect Perry to make that semi-finalist list and therefore won't make the Hall, but he at least should be discussed. Based on his ability to both stop the run and get after the quarterback is evident in his stats and he was respected by his peers, making the Sporting News or NEA All-Pro team (chosen by players and coaches) five straight years (1989-93). The media (AP, PFWA), on the other hand, only picked him in 1989 and 1990.

.

Honors

Perry was inducted into the South Carolina Football Hall of Fame in 2016 and previously, in 2002, Perry was named to the 50th Anniversary All-ACC Team. He is also in the Clemson Athletic Hall of Fame and the State of South Carolina Athletic Hall of Fame.

Maybe someday the College Football and Pro Football Hall of Fame will come knocking.

No comments:

Post a Comment