By Jeffrey J. Miller

The Buffalo

Bills of the mid-1960s were a powerhouse, earning three trips to the American

Football League championship game and two league championships. They had some pretty good players on the

offensive side of the ball, names that we all recognize like Jack Kemp, Cookie

Gilchrist, Billy Shaw, Elbert Dubenion, and many more. However, most fans, and the players

themselves, will tell anyone willing to debate that it was the Bills’ defense

that propelled the team to its pinnacle between 1964 and 1966. Boasting such names as Tom Sestak, Ron

McDole, Butch Byrd and Mike Stratton, Buffalo’s defense was formidable

indeed. Yet the most important figure on

that unit was a relatively unsung middle linebacker named Harry Jacobs. It says here that Jacobs was just

as important a figure in the team’s success, if not more so, than quarterback Kemp. After all, Jacobs was the man

calling the defensive formations during the halcyon days when the Bills put

together a three-year run in which they won 31 games while losing just nine

times, and gifted Buffalo the only major league sports championships the city as

ever known (1964 and '65).

It was with tremendous sadness that we learned that Jacobs had passed away last week (December 17, 2021) at the age of 84. His loss was a big one for Western New York and the Bills’ long-time fans, for Jacobs was not only a really good football player, but he was also an extraordinary human being. Jacobs had been battling dementia for several years but remained a steadfast supporter of the team and its alumni, even attending the reunion of the Bills’ championship teams in 2015. He had always been a very active member of alumni activities and charitable events. During his days as an active player, Jacobs was a member of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and remained a devout witness for Christ right to the very end.

For fans of the AFL-era Bills, of course, Jacobs will always be remembered primarily as the man who put personnel in position to make the plays on defense, or, as he was commonly referred, the Quarterback of the Defense. Defensive coordinator Joe Collier was the mastermind behind the Bills’ sophisticated defenses, tinkering with myriad formations, blitzes and stunts, but worked closely with his middle linebacker to make Buffalo’s unit the best in the American Football League by 1964. Jacobs was acknowledged as a full-fledged member of the defensive game-planning team, often studying film alongside Collier and devising schemes that were to be used against upcoming opponents.

“Joe broke films down,” Jacobs recalled in an interview with this writer for the book Rockin’ The Rockpile: The Buffalo Bills of the American Football League. “He was the first person to my knowledge that really worked at breaking down each of the plays so I could see how first, second, third, every down and position, what they use, and then make a choice in that situation on the field. In order to do that, I had to know what everybody else did.” This knowledge allowed Jacobs full authority to make all the defensive calls without need of consultation with the Bills’ sideline. He was the one who called the line stunts (called “exits”) or sent George Saimes in on the safety blitz. He is also the one credited with putting linebacker Mike Stratton in position to inflict the famous “Hit Heard ‘Round the World” tackle on Keith Lincoln in the 1964 AFL Championship Game. If the Buffalo's defensive record between 1964 and 1966 is any indication, the coaching staff’s faith in Jacobs was more than justified.

Jacobs was born and raised in Canton, Illinois, and attended Canton high School. He was a two-way star at Bradley University in nearby Peoria, playing guard on offense and defensive end on defense. After his senior year, Jacobs was selected to play in the Chicago Tribune All Star game, where his coach was Lou Saban of Northwestern. He went undrafted, and had unsuccessful tryouts with the Detroit Lions and Chicago Bears, both of which wanted him to play guard. “Fortunately for me,’ said Jacobs, “the AFL had just started, and Lou Saban stepped in.” Saban had been hired as the coach of the Boston Patriots franchise in the new American Football League, and brought Jacobs in to play defensive end and middle linebacker. Things were going well in Boston until Saban was let go and replaced by Mike Holovak.

“I liked it in Boston,” Jacobs recalled. “Holovak took over and they drafted Nick Buoniconti from Notre Dame. He was not—in my opinion—better than I was, but Mike put him in there. Nick turned into a great linebacker, but at that point, he wasn’t. That was really frustrating to me, so I was very pleased to come to Buffalo.”

The Patriots sold Jacobs to the Bills on July 19, 1963, where he was reunited with Saban and defensive coordinator Joe Collier. Jacobs was installed as the starting middle linebacker and held down the position for the next seven seasons. Often referred to as the Baby-Faced Assassin for his youthful looks, Jacobs pulled a complete Jeckyl-and-Hyde routine when he put his helmet on and trotted onto the field. Though he stood only six-foot, one inch, and tipped the scales at a mere 226 pounds, Jacobs was a solid performer at the Mike (middle linebacker) position, missing just ten games due to injury during his Buffalo tenure. He was part of a linebacking corps (along with outside backers John Tracey and Mike Stratton) that started 62 consecutive games, a pro football record. He was also the leader of a defensive unit that between 1964 and ’65 went 17 straight games (16 regular season and one playoff) without surrendering a rushing touchdown—another record that still stands. Jacobs also served as a mentor for Marty Schottenheimer, the Bills’ backup middle linebacker who went on to great success as a head coach in the NFL.

Jacobs discussing strategy on the Bills' sideline with

backup middle linebacker and future head coach

Marty Schottenheimer (57). November 10, 1968.

His greatest game might have been the 1965 AFL Championship Game, played December 26, 1965, at Balboa Stadium against the San Diego Chargers. In a rematch of the previous year’s title game, the Chargers were heavily favored, with their explosive offense that included the likes of Lance Alworth, Keith Lincoln, Paul Lowe and John Hadl. But with Jacobs calling the shots, the Bills’ defense pitched a shutout (23-0), with Jacobs contributing an interception in the rout.

He remained with the Bills through the 1969 season, in which he was voted into his first AFL All-Star Game (he had played in the 1965 classic, but as a member of the entire Bills squad that faced the rest of the league’s stars). Jacobs was traded to the New Orleans Saints and played one last season (1970) in the Big Easy. He was the only player to have participated in the very first and the very last games in AFL history, and is one of only 20 players to have played every season of the league’s ten-year existence.

Jacobs was also a

successful businessman, founding the firm The Jacobs Team in the Buffalo suburb

of Hamburg. The Jacobs Team, as he

explained it, “Our business is helping businesses build succession for the

future. It means building teams within

the confines of an organization so that when they shift owners (through retirement,

for example), they have built a team inside of the business that will sustain

the business.”

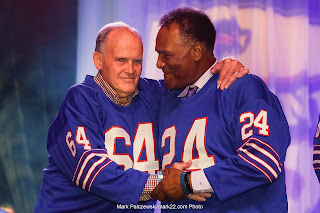

Jacobs embraces teammate Booker Edgerson at the

reunion of Buffalo's AFL championship teams, held

in 2015. Photo courtesy of Mark Palczewski.

Harry and his wife of 63 years, Kay, who survives him, remained in Western New York until his death. He was enshrined in the Greater Peoria Sports Hall of Fame in 1982, and the Greater Buffalo Sports Hall of Fame in 2012.

He was a pillar of strength for buffalo it seems. RIP Harry.

ReplyDeleteHarry Jacobs was a true gentleman. I was fortunate to know him in his later life. A great player and an even better human being. He is missed.

ReplyDeleteCouldn't agree more.

ReplyDelete